Additionally the work was honoured with the Translation by a Diploma of Merit in Melbourne in 1880 and a Gold Medal in Paris (1881), “For Services rendered to the Cause of Horology.”. In 1867 the work was honoured with a First Class Medal and a Gold Medal and Honourable Mention followed in 1868. It is first and foremost a technical book giving a broad and detailed description of what it calls a “mechanical art”. The contributions (and the subsequent translation) of the Treatise on Modern Horology made to the field of horology didn’t go unnoticed by the wider Horological community. We believe the present volume well supplies the first of these wants as regards the science and art of the subject”

“In all the mechanical industries great efforts are being made at the present day in the cause of technical education, but in order that such efforts may be successful it is the first importance that sound textbooks and competent teachers should be provided. The translators of the Treatise are well aware of this and see their contributions as but one of the sources for anyone vaguely interested in horology to rely on and draw learnings from. As with many professions, the transmission of knowledge relies on a combination of formal written knowledge and practical hands on experience provided by ones teachers. You could be reading about the force transmitted by trains or the theoretical sizes of balances, either way the reader can sense the enthusiasm to pass down the knowledge and share the ‘tricks of the trade’ so to speak, with the next generation of watchmakers and watch enthusiasts. In this case it’s refreshing to see such a well regarded book look beyond the inherent use of these mechanical instruments and to also promote the artistic and emotional elements behind horology. There’s a tendency to look back and view 19th and early 20th century clocks and watches solely for their utilitarian function of time telling. Initially published in 1861, this edition was published in 1887 by Crosby Lockwood and Co. Side note: Assay offices test the purity of precious metals, and are often associated with coinage Mints). Translated from the French of Claudius Saunier, the Ex-Director of the School of Horology at Macon (Académie de Mâcon), by Julien Tripplin (Besançon Watch Manufacturer) and Edward Rigg (Assay in the Royal Mint).

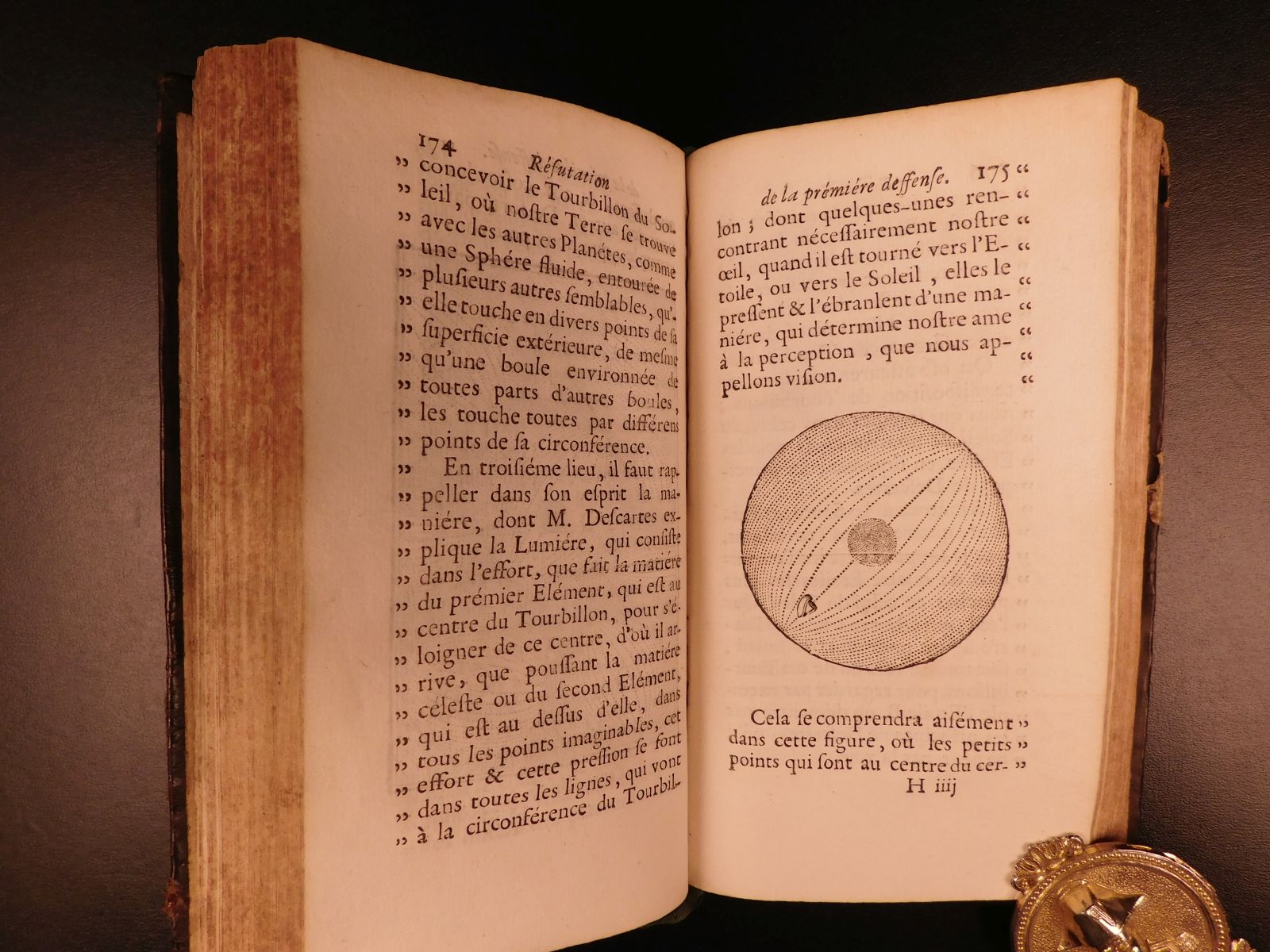

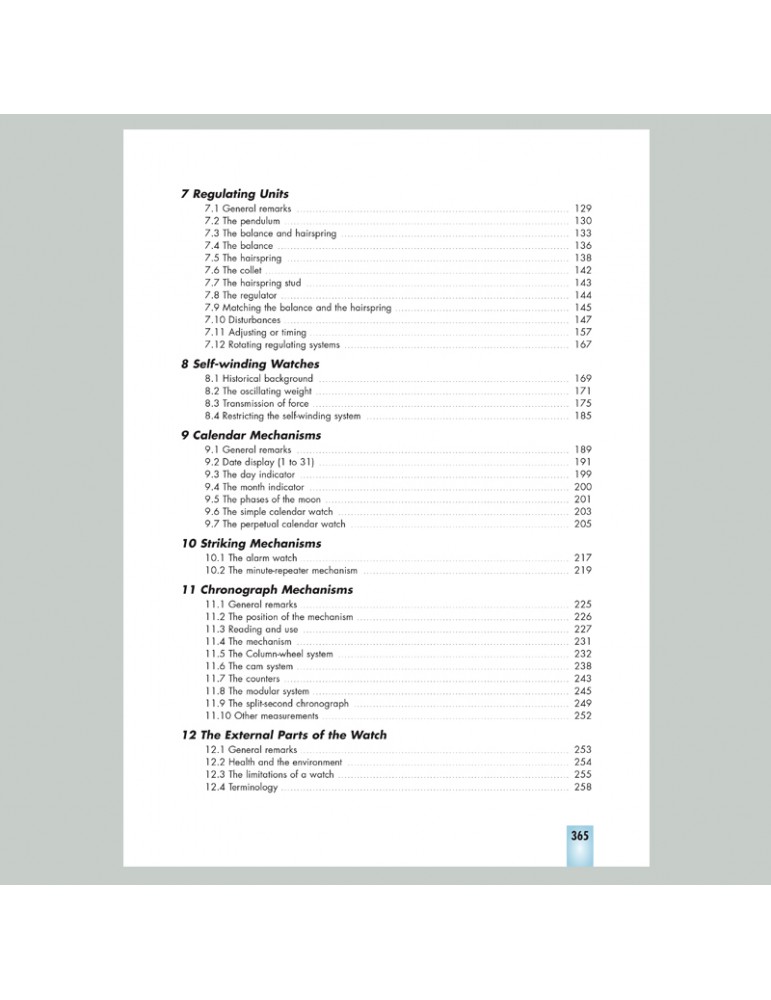

In addition to the comprehensive technical information contained within, the seventy eight woodcut and twenty two copper plate drawings are a real delight. Coming in at over 2 kgs and over 800 pages, Treatise on Modern Horology Theory and Practice is a hefty book that, aside from the intimidating size, is well worth taking a look at.

It’s easy to forget that sometimes – especially when it comes to an old profession such as watchmaking – the best information can be found by hitting the books.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)